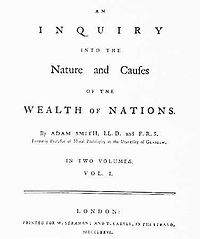

Adam Smith (baptised June 5 (OS) or June 16 (NS) 1723; died July 17, 1790) was a Scottishmoral philosopher and a pioneering political economist. One of the key figures of the intellectual movement known as the Scottish Enlightenment, he is known primarily as the author of two treatises: The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), and An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776). The latter was one of the earliest attempts to systematically study the historical development of industry and commerce in Europe, as well as a sustained attack on the doctrines of mercantilism; it also contained Smith's explanation of how rational self-interest and competition can lead to common well-being.[Neutrality disputed — See talk page]economics and provided one of the best-known intellectual rationales for free trade and capitalism. Smith's work helped to create the modern academic discipline of

Contents |

Biography

Smith was a son of the controller of the customs at Kirkcaldy, Fife, Scotland. The exact date of Smith's birth is unknown, but he was baptized at Kirkcaldy on June 5, 1723, his father having died some six months previously. At around the age of 4, he was kidnapped by a band of Gypsies, but he was quickly rescued by his uncle and returned to his mother. Smith's biographer, John Rae, commented wryly that he feared Smith would have made "a poor Gypsy".[2] There is no record of Smith having any siblings.

Education

At the age of fourteen, Smith entered the University of Glasgow , where he studied moral philosophy under "the never-to-be-forgotten " (as Smith called him) Francis Hutcheson. Here Smith developed his strong passion for liberty, reason, and free speech. In 1740 he was awarded the Snell Exhibition and entered Balliol College, Oxford, but as William Robert Scott has said, "the Oxford of his time gave little if any help towards what was to be his lifework," and he left the university in 1746. In Book V of The Wealth of Nations, Smith comments on the low quality of instruction and the meager intellectual activity at Scottish universities when compared to their English counterparts. He attributed this both to the rich endowments of the colleges at Oxford and Cambridge, which made the income of professors independent of their ability to attract students, and to the fact that distinguished men of letters could make an even more comfortable living as ministers of the Church of England.

Career in Edinburgh and Glasgow

In 1748 Smith began delivering public lectures in Edinburgh under the patronage of the Lord Kames. Some of these dealt with rhetoric and belles-lettres, but later he took up the subject of "the progress of opulence," and it was then, in his middle or late 20s, that he first expounded the economic philosophy of "the obvious and simple system of natural liberty" which he was later to proclaim to the world in his Wealth of Nations. In about 1750 he met the philosopher David Hume, who was his senior by over a decade. The alignments of opinion that can be found within the details of their respective writings covering history, politics, philosophy, economics, and religion indicate that they both shared a closer intellectual alliance and friendship than with the others who were to play important roles during the emergence of what has come to be known as the Scottish Enlightenment;[3] he frequented The Poker Club of Edinburgh.

In 1751 Smith was appointed chair of logic at the University of Glasgow, transferring in 1752 to the Chair of Moral Philosophy, once occupied by his famous teacher, Francis Hutcheson. His lectures covered the fields of ethics, rhetoric, jurisprudence, political economy, and "police and revenue". In 1759 he published his The Theory of Moral Sentiments, embodying some of his Glasgow lectures. This work, which established Smith's reputation in his day, was concerned with how human communication depends on sympathy between agent and spectator (that is, the individual and other members of society). His analysis of language evolution was somewhat superficial, as shown only 14 years later by a more rigorous examination of primitive language evolution by Lord Monboddo in his Of the Origin and Progress of Language.[4] Smith's capacity for fluent, persuasive, if rather rhetorical argument, is much in evidence. He bases his explanation not, as the third Lord Shaftesbury and Hutcheson had done, on a special "moral sense"; nor, as Hume did, on utility; but on sympathy.

Smith now began to give more attention to jurisprudence and economics in his lecture and less to his theories of morals. An impression can be obtained as to the development of his ideas on political economy from the notes of his lectures taken down by a student in about 1763 which were later edited by Edwin Cannan,[5] and from what Scott, its discoverer and publisher, describes as "An Early Draft of Part of The Wealth of Nations", which he dates about 1763. Cannan's work appeared as Lectures on Justice, Police, Revenue and Arms. A fuller version was published as Lectures on Jurisprudence in the Glasgow Edition of 1776.

Tour of France

In 1762 the academic senate of the University of Glasgow conferred on Smith the title of Doctor of laws (LL.D.). At the end of 1763, he obtained a lucrative offer from Charles Townshend (who had been introduced to Smith by David Hume), to tutor his stepson, the young Duke of Buccleuch. Smith subsequently resigned from his professorship and from 1764-66 traveled with his pupil, mostly in France, where he came to know intellectual leaders such as Turgot, Jean D'Alembert, André Morellet, Helvétius and, in particular, Francois Quesnay, the head of the Physiocratic school whose work he respected greatly. On returning home to Kirkcaldy Smith was elected fellow of the Royal Society of London and he devoted much of the next ten years to his magnum opus, The Wealth of Nations, which appeared in 1776. The book was very well received and made its author famous.

Later years

In 1778 Smith was appointed to a post as commissioner of customs in Scotland and went to live with his mother in Edinburgh. In 1783 he became one of the founding members of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and from 1787 to 1789 he occupied the honorary position of Lord Rector of the University of Glasgow. He died in Edinburgh on July 17, 1790, after a painful illness and was buried in the Canongate Kirkyard.

Smith's literary executors were two old friends from the Scottish academic world; the physicist and chemist Joseph Black, and the pioneering geologist James Hutton. Smith left behind many notes and some unpublished material, but gave instructions to destroy anything that was not fit for publication. He mentioned an early unpublished History of Astronomy as probably suitable, and it duly appeared in 1795, along with other material, as Essays on Philosophical Subjects. Contemporary followers of Adam Smith include John Millar.

Personal character and views

Not much is known about Smith's personal views beyond what can be deduced from his published works. All of his personal papers were destroyed after his death. He never married and seems to have maintained a close relationship with his mother, with whom he lived after his return from France and who predeceased him by only six years. Contemporary accounts describe Smith as an eccentric but benevolent intellectual, comically absent minded, with peculiar habits of speech and gait and a smile of "inexpressible benignity."[6] His patience and tact are said to have been valuable to his work as a university administrator at Glasgow. After his death it was discovered that much of his income had been devoted to secret acts of charity.

There has been considerable scholarly debate about the nature of Adam Smith's religious views. Smith's father had a strong interest in Christianity[7] and belonged to the moderate wing of the Church of Scotland (the national church of Scotland since 1690). Smith may have gone to England with the intention of a career in the Church of England: this is controversial and depends on the status of the Snell Exhibition. At Oxford, Smith rejected Christianity and it is generally believed that he returned to Scotland as a Deist.[8]

Economist Ronald Coase, however, has challenged the view that Smith was a Deist, stating that, whilst Smith may have referred to the "Great Architect of the Universe", other scholars have "very much exaggerated the extent to which Adam Smith was committed to a belief in a personal God". He based this on analysis of a remark in The Wealth of Nations where Smith writes that the curiosity of mankind about the "great phenomena of nature" such as "the generation, the life, growth and dissolution of plants and animals" has led men to "enquire into their causes". Coase notes Smith's observation that: "Superstition first attempted to satisfy this curiosity, by referring all those wonderful appearances to the immediate agency of the gods." Smith's close friend and colleague David Hume, with whom he agreed on most matters, is usually described as an Atheist, rather than a Deist.

Works

Shortly before his death, Smith had nearly all his manuscripts destroyed. In his last years he seemed to have been planning two major treatises, one on the theory and history of law and one on the sciences and arts. The posthumously published Essays on Philosophical Subjects (1795) probably contain parts of what would have been the latter treatise.

Wealth of Nations

The Wealth of Nations was Smith's most influential work, and is considered to be very important in the creation of the field of economics and its development into an autonomous systematic discipline. In the Western world, it is arguably the most influential book on the subject ever published.[Neutrality disputed — See talk page] The work is also the first comprehensive defense of free market policies.[citation needed] When the book, which has become a classic manifesto against mercantilism (the theory that large reserves of bullion are essential for economic success), appeared in 1776, there was a strong sentiment for free trade in both Britain and America. This new feeling had been born out of the economic hardships and poverty caused by the American War of Independence. However, at the time of publication, not everybody was immediately convinced of the advantages of free trade: the British public and Parliament still clung to mercantilism for many years to come.

The Wealth of Nations also rejects the Physiocratic school's emphasis on the importance of land; instead, Smith believed labour was paramount, and that a division of labour would effect a great increase in production.[Neutrality disputed — See talk page] One example he used was the making of pins. One worker could probably make only twenty pins per day. But if ten people divided up the eighteen steps required to make a pin, they could make a combined amount of 48,000 pins in one day. However, Smith also concluded that excessive division of labor would negatively affect worker's intellect through the carrying out of monotonous and repetetive tasks and hence he called for the establishment of a public education system.[citation needed]

Nations was so successful, in fact, that it led to the abandonment of earlier economic schools, and later economists, such as Thomas Malthus and David Ricardo, focused on refining Smith's theory into what is now known as classical economics.[citation needed] Both Modern economics and, separately, Marxian economics owe significantly to classical economics. Malthus expanded Smith's ruminations on overpopulation, while Ricardo believed in the "iron law of wages"—that overpopulation would prevent wages from topping the subsistence level. Smith postulated an increase of wages with an increase in production, a view considered more accurate today.[citation needed]

One of the main points of The Wealth of Nations is that the free market, while appearing chaotic and unrestrained, is actually guided to produce the right amount and variety of goods by a so-called "invisible hand".[Neutrality disputed — See talk page] The image of the invisible hand was previously employed by Smith in Theory of Moral Sentiments, but it has its original use in his essay, "The History of Astronomy". If a product shortage occurs, for instance, its price rises, creating a profit margin that creates an incentive for others to enter production, eventually curing the shortage. If too many producers enter the market, the increased competition among manufacturers and increased supply would lower the price of the product to its production cost, the "natural price".

Even as profits are zeroed out at the "natural price", there would be incentives to produce goods and services, as all costs of production, including compensation for the owner's labour, are also built into the price of the goods. If prices dip below a zero profit, producers would drop out of the market; if they were above a zero profit, producers would enter the market. Smith believed that while human motives are often selfishness and greed, the competition in the free market would tend to benefit society as a whole by keeping prices low, while still building in an incentive for a wide variety of goods and services.[Neutrality disputed — See talk page] Nevertheless, he was wary of businessmen and argued against the formation of monopolies.

Smith vigorously attacked the antiquated government restrictions which he thought were hindering industrial expansion. In fact, he attacked most forms of government interference in the economic process, including tariffs, arguing that this creates inefficiency and high prices in the long run.[Neutrality disputed — See talk page] This theory, now referred to as "laissez-faire", which means "let them do" or more relevant to the study of economics, "let the market set supply and demand with no interference". It is believed that this theory influenced government legislation in later years, especially during the 19th century. (However this was not an anarchistic opposition to government. Smith advocated a Government that was active in sectors other than the economy: he advocated public education of poor adults; institutional systems that were not profitable for private industries; a judiciary; and a standing army.)

Two of the most famous and often-quoted passages in The Wealth of Nations are:[Neutrality disputed — See talk page]

"It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages."

"As every individual, therefore, endeavours as much as he can both to employ his capital in the support of domestic industry, and so to direct that industry that its produce may be of the greatest value; every individual necessarily labours to render the annual value of society as great as he can. He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry, he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it. I have never known much good done by those who affected to trade for the public good. It is an affectation, indeed, not very common among merchants, and very few words need be employed in dissuading them from it."

Another favorite quote, usually recited by economists, also from The Wealth of Nations is:

"People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices. It is impossible indeed to prevent such meetings, by any law which either could be executed, or would be consistent with liberty and justice. But though the law cannot hinder people of the same trade from sometimes assembling together, it ought to do nothing to facilitate such assemblies; much less to render them necessary."

Smith postulated four "maxims" of taxation: proportionality, transparency, convenience and efficiency. Smith is credited by economists as one of the first to advocate a progressive tax.[9] Smith wrote, "It is not very unreasonable that the rich should contribute to the public expense, not only in proportion to their revenue, but something more in proportion." In another quote he supported taxation in proportion to the revenue (income) of the individual:

"The subjects of every state ought to contribute towards the support of the government, as nearly as possible, in proportion to their respective abilities; that is, in proportion to the revenue which they respectively enjoy under the protection of the state. The expense of government to the individuals of a great nation is like the expense of management to the joint tenants of a great estate, who are all obliged to contribute in proportion to their respective interests in the estate. In the observation or neglect of this maxim consists what is called the equality or inequality of taxation."

The "Adam Smith-Problem"

| The Liberalism series, part of the Politics series |

|---|

| Portal:Politics |

In the Wealth of Nations Smith claims that self-interest alone (in a proper institutional setting) can lead to socially beneficial results. But in his Theory of Moral Sentiments Smith argues that sympathy is required to achieve socially beneficial results. On the surface it appears that a contradiction exists. Economist August Oncken referred to this as 'the Adam-Smith-Problem'.[10]Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter also emphasized this apparent contradiction in his commentary on Smith's work.

Adam Smith himself cannot have seen any contradiction, since he produced a revised edition of Moral Sentiments after the publication of Wealth of Nations. Both sets of ideas are to be found in his Lectures on Jurisprudence. In recent years most students of Adam Smith's work have argued that no contradiction exists. In the Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith develops a theory of psychology in which individuals in society find it in their self-interest to develop sympathy as they seek approval of what he calls the "impartial spectator." The self-interest he speaks of is not a narrow selfishness but something that involves sympathy.

Some readers of The Wealth of Nations have assumed that when Smith speaks of "self-interest" he is referring to selfishness. Although in some contexts, such as buying and selling, sympathy generally need not be considered, Smith makes it clear that he regards selfishness as inappropriate, if not immoral, and that the self-interested actor has sympathy for others. In The Theory of Moral Sentiments Smith argues that the self-interest of any actor includes the interest of the rest of society, since the socially-defined notions of appropriate and inappropriate actions necessarily affect the interests of the individual as a member of society. Context is also useful as Adam Smith was against the idea of corporations, or "joint stock companies."

In any case, Adam Smith apparently believed that moral sentiments and self-interest would always add up to the same thing. One possible line of reasoning he might have employed in reaching this conclusion is as follows: the invisible hand cannot operate if there is no society, for precluding a societal construct precludes division of labor, and thus, the efficiency which comes with its manifestation. Now for society to exist, justice is a necessary condition (as pointed out in Smith's Theory of Moral Sentiments). For justice to exist in any social setting, individuals must harbor the passions of gratitude and resentment governed by a sense of 'merit' and 'demerit' (again from Smith's Theory of Moral Sentiments). And finally, as Smith himself would have so vehemently argued, the sense of 'merit' and 'demerit' is almost exclusively engendered by human sympathy. In conclusion, the invisible hand of the market is, at some level, contingent upon the ability of humans to sympathize: Smith's self-interest is indeed in consonance with the notion of sympathy.

Influence

The Wealth of Nations, one of the earliest attempts to study the rise of industry and commercial development in Europe, was a precursor to the modern academic discipline of economics. It provided one of the best-known intellectual rationales for free trade and capitalism, greatly influencing the writings of later economists. David Ricardo and Karl Marx were influenced by economic theories of Adam Smith. Smith was ranked #30 in Michael H. Hart's list of the most influential figures in history.[*]

From 13 March 2007 onwards Smith's portrait appeared in the UK on new £20 notes. He is the first Scotsman to feature on a currency issued by the Bank of England.[11] A picture of the note is available on the Bank of England website.[12] However, many actors in academia and in the real world have and are acknowledging that they or others have misinterpreted the works of Adam Smith, with some arguing that Adam Smith's legacy has been "lost".

In a journal article, "The Rise of Adam Smith: Articles and Citations, 1970-1997", economist Jonathan B. Wight reports that only two articles on Adam Smith or his works were published the year before 1971. In 2002 Wight, the author of this paper and of other books and articles on Adam Smith and his works, reports that six hundred articles and thirty books were published in the twenty seven years between 1970 and 1997. A heightened interest in Adam Smith and his works has been sustained. And, this trend Wight writes is more than a "speculative bubble" in a 2004 conference paper titled "Is There a Speculative Bubble in Scholarship on Adam Smith?", presented at the Eleventh World Congress of Social Economics, Albertville, France.

The bicentennial anniversary of the publication of the Wealth of Nations was celebrated in 1976. Results of this celebration has been increased interest in Smith's first book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, and in his other works, throughout academia. This heightened interest in his book on moral philosophy has also been sustained. Or, assome say, in 1976 there was a break with the earlier emphasis on an Adam Smith problem. After 1976 Adam Smith was more likely to be represented as the author of both the Wealth of Nations and The Theory of Moral Sentiments and thereby as the founder of a moral philosophy and the science of economics. His "economic man" or actor was also more often represented as a moral person. Finally, also pointed to was his opposition to slavery, colonialism, and empire or his statements about high wages for the poor, his views that the porter was not intellectually inferior to the porter (Levy,Peart). And, more than one author refer to a need to recover "Adam Smith's lost legacy" (Kennedy, West).

In line with such trends, on January 24, 2008 Bill Gates said the following at the world economic forum in Davos Switzerland "Adam Smith, the very father of capitalism and the author of “Wealth of Nations,” who believed strongly in the value of self-interest for society, opened his first book with the following lines: "How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortunes of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it, except the pleasure of seeing it."

Expressing his interest in reducing poverty in 2008, he spoke about a "creative" rather than an "unfettered" or laissez faire, capitalism. "Creative capitalism takes this interest in the fortunes of others and ties it to our interest in our own fortunes in ways that help advance both. This hybrid engine of self-interest and concern for others can serve a much wider circle of people than can be reached by self-interest or caring alone."[13] Nearly two years before, Gate's interest in Adam Smith was also evident. On June 25, 2006, Gates presented a copy of Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations to Warren Buffett after Buffett announced that he would donate his wealth to The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, [14].[14]

There, in addition, has been a controversy over the extent of Smith's originality in The Wealth of Nations. Some argue that the work added only modestly to the already established ideas of thinkers such as Anders Chydenius (The National Gain 1765), David Hume and the Baron de Montesquieu. Indeed, many of the theories Smith set out simply described historical trends away from mercantilism and towards free trade that had been developing for many decades and had already had significant influence on governmental policy. Nevertheless, Smith's work organized their ideas comprehensively, and so remains one of the most influential and important books in the field today.

Herbert Stein, in a frequently-quoted article, "Adam Smith did not wear an Adam Smith necktie," wrote that the people who wear the Adam Smith tie do it "to make a statement of their devotion to the idea of free markets and limited government. What stands out in the Wealth of Nations, however, is that their patron saint was not pure or doctrinaire about this idea. He viewed government intervention in the market with great skepticism. He regarded his exposition of the virtues of the free market as his main contribution to policy, and the purpose for which his economic analysis was developed.

"Yet he was prepared to accept or propose qualifications to that policy in the specific cases where he judged that their net effect would be beneficial and would not undermine the basically free character of the system," wrote Stein. "He did not wear the Adam Smith necktie." In Stein's reading, The Wealth of Nations could justify the Food and Drug Administration, The Consumer Product Safety Commission, mandatory employer health benefits, environmentalism, and "discriminatory taxation to deter improper or luxurious behavior."[15][16]

Interpreting Adam Smith

Vivienne Brown has alleged that in the 20th century USA, Reaganomics supporters, The Wall Street Journal and other similar sources, have spread among the general public, a partial and misleading vision of Adam Smith, portrayed as an "extreme dogmatic defender of laissez-faire[17][18] capitalism and supply-side economics".

According to Brown and Pack, Smith's position was very close to what is currently perceived in the USA as a "liberal democrat,". In The Wealth of Nations Smith advocates government economic intervention with the allocation of many economic functions, they say. In this analysis, Smith instead attacked the corrupted favoritism made by the governments in favor of the rich and powerful and against the poor.[17] [18]

Major works

- The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759)

- An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776)

- Essays on Philosophical Subjects (published posthumously 1795)

- Lectures on Jurisprudence (published posthumously 1976)

- Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres

Critics of Adam Smith

- Arthur Lee, An Essay in Vindication Of The Continental Colonies Of America, From A Censure of Mr. Adam Smith, in His Theory of Moral Sentiments. With Some Reflections on Slavery in General. By an American 1764 [19]

- Thomas Carlyle [20]

- Charles Dickens,Ibid., [21]

- John Ruskin, Ibid.

References

- Robert Falkner (1997). Biography of Smith (English). Liberal Democrat History Group. Retrieved on September 10, 2007.

- Powell, Jim (March 1995). "Adam Smith-'I had almost forgot that I was the author of the inquiry concerning The Wealth of Nations'". The Freeman 45 (3). Foundation for Economic Education. Retrieved on 2008-01-01.

- Donald Winch, ‘Smith, Adam (bap. 1723, d. 1790) ’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004

- Cloyd, E.L.: "James Burnett, Lord Monboddo", pp 64-66. Oxford University Press, 1972

- "Lectures on Justice, Police, Revenue and Arms", 1896

- Liberty Fund. Chapter XVII - London (English). Ch. 17. Liberty Fund. Retrieved on September 10, 2007.

- Ross, Ian Simpson, The Life of Adam Smith page 15

- "When the time of his residence at Oxford expired, the question arose what line he was afterwards to pursue. He was destitute of patrimony and had not any turn for business. The Church seemed an improper profession, because he had early become a disciple of Voltaire in matters of religion." Times obituary of Adam Smith

- Do Americans Still Believe In Sharing The Burden? Robert B. Reich, Washington Post , Apr 26, 1987

- August Oncken, "The Consistency of Adam Smith," The Economic Journal 7, no. 27 (1897): 444.

- BBC News (2006). Smith replaces Elgar on £20 note (English). BBC News. Retrieved on September 10, 2007.

- Bank of England. Bank of England Banknotes - Virtual Tour (English). Bank of England. Retrieved on September 10, 2007.

- “A New Approach to Capitalism in the 21st Century”, Remarks by Bill Gates, Chairman, Microsoft Corporation, World Economic Forum 2008, Davos, Switzerland, Jan. 24, 2008

- a b Jeremy W. Peters (2006). Buffett Always Planned to Give Away His Billions (English). New York Times. Retrieved on September 10, 2007.

- Stein, Herbert (1994, April 6). "Board of Contributors: Remembering Adam Smith". Wall Street Journal (Eastern Edition), p. PAGE A14. Retrieved January 8, 2008, from Wall Street Journal database. (Document ID: 28143064).

- Marc Lee (2006). Adam Smith did not wear an Adam Smith necktie (English). progecon blog. Retrieved on September 10, 2007.

- a b Brown, Vivienne (1993) The Economic Journal, Vol. 103, No. 416 (Jan., 1993), pp. 230-232 doi:10.2307/2234351

- a b Pack, Spencer J. (1991) Capitalism as a Moral System: Adam Smith's Critique of the Free Market Economy

- An Essay in Vindication Of The Continental Colonies Of America, From A Censure of Mr. Adam Smith, in His Theory of Moral Sentiments. With Some Reflections on Slavery in General. By an American by Arthur Lee, 1764

- The Origin of the Term "Dismal Science" to Describe Economicsby Robert Dixon

- The Secret History of the Dismal Science: Economics, Religion and Race in the 19th Century by economists David Levy and Sandra Peart

Bibliography

- James Buchan. The Authentic Adam Smith: His Life and Ideas (2006)

- Stephen Copley and Kathryn Sutherland, eds. Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations: New Interdisciplinary Essays (1995)

- F. Glahe, ed. Adam Smith and the Wealth of Nations: 1776-1976 (1977)

- Knud Haakonssen. The Cambridge Companion to Adam Smith (2006)

- Samuel Hollander. The Economics of Adam Smith (University of Toronto Press) (1973)

- Muller, Jerry Z. Adam Smith in his Time and Ours: Designing the Decent Society. Princeton Univ. Press (1995)

- Muller, Jerry Z. The Mind and the Market: Capitalism in Western Thought. Anchor Books (2002)

- James Otteson. Adam Smith's Marketplace of Life (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

- James Otteson. "The Recurring 'Adam Smith Problem,'" History of Philosophy Quarterly 17, 1 (January 2000): 51–74.

- Frederick Rosen, Classical Utilitarianism from Hume to Mill (Routledge Studies in Ethics & Moral Theory), 2003. ISBN 0415220947

- P. J. O'Rourke. On The Wealth of Nations (Books That Changed the World) (2006)

- Richard F. Teichgraeber. Free Trade and Moral Philosophy: Rethinking the Sources of Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations (1986)

- This article incorporates public domain text from: Cousin, John William (1910). A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London, J.M. Dent & sons; New York, E.P. Dutton.

External links

- General

- Biography at the Concise Encyclopedia of Economics

- Adam Smith's page at MetaLibri

- Life of Adam Smith by John Rae, at the Library of Economics and Liberty

- The Celebrated Adam Smith by Murray N. Rothbard; full text of Chapter 16 of An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought, Vol. I and II, Edward Elgar, 1995; Mises Institute 2006

- Smith's works

- Brad deLong's Adam Smith page

- The Adam Smith Institute

- Grave of Adam Smith on the Famous Economists Grave Sites

- Adam Smith - Important Scots

- Reflections on Smith's ethicsPDF (129 KiB)

- Adam Smith on the 50 British Pound (Clydesdale Bank) banknote

- "The Betrayal of Adam Smith" by David C. Korten

- Adam Smith - A Primer by Eamonn Butler. Introduction to Smith's work, free download

- An Essay In Vindication Of The Continental Colonies Of America,From A Censure of Mr Adam Smith, in His Theory of Moral Sentiments. With Some Reflections on Slavery in General.By an American,1764

- Timeline of the Life of Adam Smith (1723-1790) at the Online Library of Liberty

- Timeline of the Scottish Enlightenment at the Online Library of Liberty

- Works

- Works by Adam Smith at Project Gutenberg

- An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations at MetaLibri Digital Library (PDF)

- The Theory of Moral Sentiments at MetaLibri Digital Library

- The Theory of Moral Sentiments at the Library of Economics and Liberty

- The Wealth of Nations at the Library of Economics and Liberty. Cannan edition. Definitive, fully searchable, free online

- The Wealth of Nations, available at Project Gutenberg.

- The Wealth of Nations from Mondo Politico Library - full text; formatted for easy on-screen reading

- The Wealth of Nations from the Adam Smith Institute - elegantly formatted for on-screen reading

- Works and Correspondence of Adam Smith. Glasgow edition, 7 volumes at the Online Library of Liberty. Definitive, free online

Adam Smith

The Theory of the Moral Sentiments

1759

Adam Smith

An Inquiry into the Nature And Causes of the Wealth of Nations

1776

BOOK ONE - OF THE CAUSES OF IMPROVEMENT IN THE PRODUCTIVE POWERS OF LABOUR, AND OF THE ORDER ACCORDING TO WHICH ITS PRODUCE IS NATURALLY DISTRIBUTED AMONG THE DIFFERENT RANKS OF THE PEOPLE.

Book One Introduction

Chapter 1 - Of The Division of Labour

Chapter 2 - Of the Principle which gives occasion to the Division of Labour

Chapter 3 - That the Division of Labour is limited by the Extent of the Market

Chapter 4 - Of the Origin and Use of Money

Chapter 5 - Of the Real and Nominal Price of Commodities, or their Price in Labour, and their Price in Money

Chapter 6 - Of the Component Parts of the Price of Commodities

Chapter 7 - Of the Natural and Market Price of Commodities

Chapter 8 - Of the Wages of Labour

Chapter 9 - Of the Profits of Stock

Chapter 10 - Of Wages and Profit in the different Employments of Labour and Stock

Chapter 10 - Part 1 - Inequalities arising from the Nature of the Employments themselves

Chapter 10 - Part 2 - Inequalities by the Policy of Europe

Chapter 11 - Of the Rent of Land

Chapter 11 - Part 1 - Of the Produce of Land which always affords Rent

Chapter 11 - Part 2 - Of the Produce of Land which sometimes does, and sometimes does not, afford Rent

Chapter 11 - Part 3 - Of the Variations in the Proportion between the respective Values of that Sort of Produce ...

Chapter 11 - Tables referred to in Chapter 11, Part 3

Chapter 11 - Digressions concerning the variations in the value of silver during the course of the last four centuries

Chapter 11 - - - First Period

Chapter 11 - - - Second Period

Chapter 11 - - - Third Period

Chapter 11 - Variations in the proportion between the respective values of gold and silver

Chapter 11 - Grounds of the suspicion that the value of silver still continues to decrease

Chapter 11 - Different effects of the progress of improvement upon three different sorts of rude produce

Chapter 11 - - - First Sort

Chapter 11 - - - Second Sort

Chapter 11 - - - Third Sort

Chapter 11 - Conclusion of the Digression concerning variations in the value of silver

Chapter 11 - Effects of the progress of improvement upon the real price of manufactures

Chapter 11 - Conclusion of the Chapter

BOOK TWO - OF THE NATURE, ACCUMULATION, AND EMPLOYMENT OF STOCK

Book Two Introduction

Chapter 1 - Of The Division of Stock

Chapter 2 - Of Money considered as a particular Branch of the general Stock of the Society ...

Chapter 3 - Of the Accumulation of Capital, or of Productive and Unproductive Labour

Chapter 4 - Of Stock Lent at Interest

Chapter 5 - Of the Different Employment of Capitals

BOOK THREE - OF THE DIFFERENT PROGRESS OF OPULENCE IN DIFFERENT NATIONS

Chapter 1 - Of the Natural Progress of Opulence

Chapter 2 - Of the Discouragement of Agriculture in the ancient State of Europe after the Fall of the Roman Empire

Chapter 3 - Of the Rise and Progress of Cities and Towns after the Fall of the Roman Empire

Chapter 4 - How the Commerce of the Towns Contributed to the Improvement of the Country

BOOK FOUR - OF SYSTEMS OF POLITICAL ECONOMY

Book Four Introduction

Chapter 1 - Of the Principle of the Commercial, or Mercantile System

Chapter 2 - Of Restraints upon the Importation from Foreign Countries of such Goods as can be produced at Home

Chapter 3 - Of the extraordinary Restraints upon the Importation of Goods of almost all kinds from those Countries ...

Chapter 3 - Part 1 - Of the Unreasonableness of those Restraints even upon the Principles of the Commercial System

Chapter 3 - Part 1 - Digression concerning Banks of Deposit, particularly concerning that of Amsterdam

Chapter 3 - Part 2 - Of the Unreasonableness of those extraordinary Restraints upon other Principles

Chapter 4 - Of Drawbacks

Chapter 5 - Of Bounties

Chapter 5 - Digression concerning the Corn Trade and Corn Laws

Chapter 6 - Of Treaties of Commerce

Chapter 7 - Of Colonies

Chapter 7 - Part 1 - Of the Motives for establishing new Colonies

Chapter 7 - Part 2 - Causes of Prosperity of New Colonies

Chapter 7 - Part 3 - Of the Advantages which Europe has derived from the Discovery of America ... Passage to the East Indies ...

Chapter 8 - Conclusion of the Mercantile System

Chapter 9 - Of the Agricultural Systems, or of those Systems of Political Economy which represent the Produce of Land ...

BOOK FIVE - OF THE REVENUE OF THE SOVEREIGN OR COMMONWEALTH

Chapter 1 - Part 1 - Of the Expenses of the Sovereign or Commonwealth

Chapter 1 - - - Of the Expense of Defence - Militia

Chapter 1 - - - Of the Expense of Defence - Standing Army

Chapter 1 - Part 2 - Of the Expense of Justice

Chapter 1 - Part 3 - Of the Expense of Public Works and Public Institutions

Chapter 1 - Article 1 - Of the Public Works and Institutions for facilitating the Commerce of the Society ...

Chapter 1 - - - Of those which are necessary for facilitating Commerce in general

Chapter 1 - - - Of the Public Works and Institutions which are necessary for facilitating particular Branches of Commerce

Chapter 1 - - - Joint Stock Companies

Chapter 1 - Article 2 - Of the Expense of the Institutions for the Education of Youth

Chapter 1 - - - Modern Institutions for Education

Chapter 1 - - - Different Plans in Different Nations

Chapter 1 - - - Education of Women

Chapter 1 - Article 3 - Of the Expense of the Institutions for the Instruction of People of all Ages

Chapter 1 - - - Chiefly those for religious instruction

Chapter 1 - - - Austere or Liberal Schemes

Chapter 1 - - - Collation of Power in Europe to the Pope

Chapter 1 - - - Declension of the authority of the Church of Rome

Chapter 1 - - - The Lutheran and Calvinistic sects following the Reformation

Chapter 1 - - - University vs Church Benefices

Chapter 1 - - - Revenue for education

Chapter 1 - Part 4 - Of the Expense of Supporting the Dignity of the Sovereign - AND - Conclusion

Chapter 2 - Of the Sources of the General or Public Revenue of the Society

Chapter 2 - Part 1 - Of the Funds or Sources of Revenue which may peculiarly belong to the Sovereign or Commonwealth

Chapter 2 - Part 2 - Of Taxes

Chapter 2 - Article 1 - Taxes upon Rent. Taxes upon the Rent of Land

Chapter 2 - - - Taxes which are proportioned, not to the Rent, but to the Produce of Land

Chapter 2 - - - Taxes upon the Rent of House

Chapter 2 - Article 2 - Taxes on Profit, or upon the Revenue arising from Stock

Chapter 2 - - - Taxes upon Profit of particular Employments

Chapter 2 - Appendix to Articles 1 and 2 - Taxes upon the Capital Value of Land, Houses, and Stock

Chapter 2 - Article 3 - Taxes upon the Wages of Labour

Chapter 2 - Article 4 - Taxes which, it is intended, should fall indifferently upon every different Species of Revenue

Chapter 2 - - - Capitation Taxes

Chapter 2 - - - Taxes upon Consumable Commodities

Chapter 2 - - - The Mercantile System

Chapter 2 - - - Tax on Fermented and Spirituous liquors

Chapter 2 - - - Customs and Excise Duties

Chapter 2 - - - Absentee Tax

Chapter 2 - - - Taxes on Luxury Goods

Chapter 2 - - - Comparisons with other Countries

Chapter 2 - - - Administration of Tax Collecting

Chapter 3 - Of Public Debts

Chapter 3 - - - Public Borrowing

Chapter 3 - - - Defraying the cost of War

Chapter 3 - - - The rise of the Public Debt

Chapter 3 - - - Dealing with the Public Debt

Chapter 3 - - - Growth in Capital

Chapter 3 - - - Sources of Revenue

Chapter 3 - - - Inflation

Chapter 3 - - - Stamp Duties

Chapter 3 - Appendix

Democratic and Capitalistic Links to Freemasonry

Charitable effortThe fraternity is widely involved in charity and community service activities. In contemporary times, money is collected only from the membership, and is to be devoted to charitableFriendly Society, and there were elaborate regulations to determine a petitioner's eligibility for consideration for charity, according to strictly Masonic criteria. purposes. Freemasonry worldwide disburses substantial charitable amounts to non-Masonic charities, locally, nationally and internationally. In earlier centuries, however, charitable funds were collected more on the basis of a Provident or Some examples of Masonic charities include:

Membership requirementsA candidate for Freemasonry must petition a lodge in his community, obtaining an introduction by asking an existing member, who then becomes the candidate's proposer. In some jurisdictions, it is required that the petitioner ask three times, however this is becoming less prevalent.[45] In other jurisdictions, more open advertising is utilised to inform potential candidates where to go for more information. Regardless of how a potential candidate receives his introduction to a Lodge, he must be freely elected by secret ballot in open Lodge. Members approving his candidacy will vote with "white balls" in the voting box. Adverse votes by "black balls" will exclude a candidate. The number of adverse votes necessary to reject a candidate, which in some jurisdictions is as few as one, is set out in the governing Constitution of the presiding Grand Lodge. General requirementsGenerally, to be a regular Freemason, a candidate must:[19]

Deviation from one or more of these requirements is generally the barometer of Masonic regularity or irregularity. However, an accepted deviation in some regular jurisdictions is to allow a Lewis (the son of a Mason),[47] to be initiated earlier than the normal minimum age for that jurisdiction, although no earlier than the age of 18. Some Grand Lodges in the United States have an additional residence requirement, candidates being expected to have lived within the jurisdiction for certain period of time, typically six months.[48] Membership and religionFreemasonry explicitly and openly states that it is neither a religion nor a substitute for one. "There is no separate Masonic God", nor a separate proper name for a deity in any branch of Freemasonry.[49][50] Regular Freemasonry requires that its candidates believe in a Supreme Being, but the interpretation of the term is subject to the conscience of the candidate. This means that men from a wide range of faiths, including (but not limited to) Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, Sikhism, Hinduism, etc. can and have become Masons. Since the early 19th century, in the irregular Continental European tradition (meaning irregular to those Grand Lodges in amity with the United Grand Lodge of England), a very broad interpretation has been given to a (non-dogmatic) Supreme Being; in the tradition of Baruch Spinoza and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe — or views of The Ultimate Cosmic Oneness — along with Western atheistic idealism and agnosticism. Freemasonry in Scandinavia, known as the Swedish Rite, on the other hand, accepts only Christians.[9] In addition, some appendant bodies (or portions thereof) may have religious requirements. These have no bearing, however, on what occurs at the lodge level. On October 2007, in a case involving the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act of 2000 (RLUIPA) (a landmark law that says government may not infringe on religious buildings without a compelling interest) a Californian court ruled that the Scotish Rite in LA could not rent their building to outside groups under the provisions of RLUIPA. In a footnote in the decision, the court stated "We see no principled way to distinguish the earnest pursuit of these (Masonic) principles ... from more widely acknowledged modes of religious exercise." This statement has caused some to claim that the court has recognized Freemasonry as a religious institution.[51] Opposition to and criticism of Freemasonry

Anti-Masonry (alternatively called Anti-Freemasonry) is defined as "Avowed opposition to Freemasonry".[52] However, there is no homogeneous anti-Masonic movement. Anti-Masonry consists of radically differing criticisms from sometimes incompatible groups who are hostile to Freemasonry in some form. They include religious groups, political groups, and conspiracy theorists. There have been many disclosures and exposés dating as far back as the eighteenth century. These often lack context,[53] may be outdated for various reasons,[32] or could be outright hoaxes on the part of the author, as in the case of the Taxil hoax.[54] These hoaxes and exposures have often become the basis for criticism of Masonry, usually religious (mainly Roman Catholic and evangelical Christian) or political (usually Socialist or Communist dictatorial objections, but also the historical Anti-Masonic Party in the United States) in nature. The political opposition that arose after the "Morgan Affair" in 1826 gave rise to the term "Anti-Masonry", which is still in use today, both by Masons in referring to their critics and as a self-descriptor by the critics themselves. Religious oppositionFreemasonry has attracted criticism from theocratic states and organised religions for supposed competition with religion, or supposed heterodoxy within the Fraternity itself, and has long been the target of conspiracy theories, which see it as an occult and evil power. Christianity and FreemasonryAlthough members of various faiths cite objections, certain Christian denominations have had high profile negative attitudes to Masonry, banning or discouraging their members from being Freemasons. The denomination with the longest history of objection to Freemasonry is the Catholic Church. The objections raised by the Catholic Church are based on the allegation that Masonry teaches a naturalistic deistic religion which is in conflict with Church doctrine.[55] A number of Papal pronouncements have been issued against Freemasonry. The first was Pope Clement XII's In Eminenti, April 28, 1738; the most recent was Pope Leo XIII's Ab Apostolici, October 15, 1890. The 1917 Code of Canon Law explicitly declared that joining Freemasonry entailed automatic excommunication.[56] The 1917 Code of Canon Law also forbade books friendly to Freemasonry. In 1983, the Church issued a new Code of Canon Law. Unlike its predecessor, it did not explicitly name Masonic orders among the secret societies it condemns. It states in part: "A person who joins an association which plots against the Church is to be punished with a just penalty; one who promotes or takes office in such an association is to be punished with an interdict." This omission caused both Catholics and Freemasons to believe that the ban on Catholics becoming Freemasons may have been lifted, especially after the perceived liberalisation of Vatican II.[57] However, the matter was clarified when Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI), as the Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, issued Quaesitum est, which states: "...the Church’s negative judgment in regard to Masonic association remains unchanged since their principles have always been considered irreconcilable with the doctrine of the Church and therefore membership in them remains forbidden. The faithful who enroll in Masonic associations are in a state of grave sin and may not receive Holy Communion." Thus, from a Catholic perspective, there is still a ban on Catholics joining Masonic Lodges. For its part, Freemasonry has never objected to Catholics joining their fraternity. Those Grand Lodges in amity with UGLE deny the Church's claims and state that they explicitly adhere to the principle that "Freemasonry is not a religion, nor a substitute for religion."[49] In contrast to Catholic allegations of rationalism and naturalism, Protestant objections are more likely to be based on allegations of mysticism, occultism, and even Satanism.[58] Masonic scholar Albert Pike is often quoted (in some cases misquoted) by Protestant anti-Masons as an authority for the position of Masonry on these issues. However, Pike, although undoubtedly learned, was not a spokesman for Freemasonry and was controversial among Freemasons in general, representing his personal opinion only, and furthermore an opinion grounded in the attitudes and understandings of late 19th century Southern Freemasonry of the USA alone. Indeed his book carries in the preface a form of disclaimer from his own Grand Lodge. No one voice has ever spoken for the whole of Freemasonry.[59] Since the founding of Freemasonry, many Bishops of the Church of England have been Freemasons, such as Archbishop Geoffrey Fisher.[60] In the past, few members of the Church of England would have seen any incongruity in concurrently adhering to Anglican Christianity and practicing Freemasonry. In recent decades, however, reservations about Freemasonry have increased within Anglicanism, perhaps due to the increasing prominence of the evangelical wing of the church. The current Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, appears to harbour some reservations about Masonic ritual, whilst being anxious to avoid causing offence to Freemasons inside and outside the Church of England. In 2003 he felt it necessary to apologise to British Freemasons after he said that their beliefs were incompatible with Christianity and that he had barred the appointment of Freemasons to senior posts in his diocese when he was Bishop of Monmouth.[61] Regular Freemasonry has traditionally not responded to these claims, beyond the often repeated statement that those Grand Lodges in amity with UGLE explicitly adhere to the principle that "Freemasonry is not a religion, nor a substitute for religion. There is no separate 'Masonic deity', and there is no separate proper name for a deity in Freemasonry".[49] In recent years, however, this has begun to change. Many Masonic websites and publications now address these criticisms specifically. Islam and FreemasonryMany Islamic anti-Masonic arguments are closely tied with Anti-Semitism and Anti-Zionism, though other criticisms are made such as linking Freemasonry to Dajjal.[62] Some Muslim anti-Masons argue that Freemasonry promotes the interests of the Jews around the world and that one of its aims is to rebuild the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem after destroying the Al-Aqsa Mosque.[63] In article 28 of its Covenant, Hamas states that Freemasonry, Rotary, and other similar groups "work in the interest of Zionism and according to its instructions…."[64] Many countries with a significant Muslim population do not allow Masonic establishments within their jurisdictions. However, countries such as Turkey, Morocco, and Egypt have established Grand Lodges[65] while in countries such as Malaysia[66], and Lebanon[67] there are District Grand Lodges operating under a warrant from an established Grand Lodge. Political opposition

Regular Freemasonry has in its core ritual a formal obligation: to be quiet and peaceable citizens, true to the lawful government of the country in which they live, and not to countenance disloyalty or rebellion.[25] A Freemason makes a further obligation, before being made Master of his Lodge, to pay a proper respect to the civil magistrates.[25] The words may be varied across Grand Lodges, but the sense in the obligation taken is always there. Nevertheless, much of the political opposition to Freemasonry is based upon the idea that Masonry will foment (or sometimes prevent) rebellion. Conspiracy theorists have long associated Freemasonry with the New World Order and the Illuminati, and state that Freemasonry as an organisation is either bent on world domination or already secretly in control of world politics. Historically, Freemasonry has attracted criticism - and suppression - from both the politically extreme right (e.g. Nazi Germany)[68][69] and the extreme left (e.g. the former Communist states in Eastern Europe). The Fraternity has encountered both applause for supposedly founding, and opposition for supposedly thwarting, liberal democracy (such as the United States of America).[citation needed] In some countries anti-Masonry is often related to anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism. For example, In 1980, the Iraqi legal and penal code was changed by Saddam Hussein's ruling Ba'ath Party, making it a felony to "promote or acclaim Zionist principles, including Freemasonry, or who associate [themselves] with Zionist organisations."[70] Professor Andrew Prescott, of the University of Sheffield, writes: "Since at least the time of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, anti-semitism has gone hand in hand with anti-masonry, so it is not surprising that allegations that 11 September was a Zionist plot have been accompanied by suggestions that the attacks were inspired by a masonic world order."[71] In 1799 English Freemasonry almost came to a halt due to Parliamentary proclamation. In the wake of the French Revolution, the Unlawful Societies Act, 1799 banned any meetings of groups that required their members to take an oath or obligation.[72] The Grand Masters of both the Moderns and the Antients Grand Lodges called on the Prime Minister William Pitt, (who was not a Freemason) and explained to him that Freemasonry was a supporter of the law and lawfully constituted authority and was much involved in charitable work. As a result Freemasonry was specifically exempted from the terms of the Act, provided that each Private Lodge's Secretary placed with the local "Clerk of the Peace" a list of the members of his Lodge once a year.[72] This continued until 1967 when the obligation of the provision was rescinded by Parliament.[72] Freemasonry in the United States faced political pressure following the disappearance of William Morgan in 1826. Reports of the "Morgan Affair", together with opposition to Jacksonian democracy (Jackson was a prominent Mason) helped fuel an Anti-Masonic movement, culminating in the formation of a short lived Anti-Masonic Party which fielded candidates for the Presidential elections of 1828 and 1832. Even in modern democracies, Freemasonry is still sometimes accused of being a network where individuals engage in cronyism, using their Masonic connections for political influence and shady business dealings. This is officially and explicitly deplored in Freemasonry.[25] It is also charged that men become Freemasons through patronage or that they are offered incentives to join. This is not the case; no one lodge member may control membership in the lodge and in order to start the process of becoming a Freemason, an individual must ask to join the Fraternity "freely and without persuasion."[25] In Italy, Freemasonry has become linked to a scandal concerning the Propaganda Due Lodge (aka P2). This Lodge was Chartered by the Grande Oriente d'Italia in 1877, as a Lodge for visiting Masons unable to attend their own lodges. Under Licio Gelli’s leadership, in the late 1970s, the P2 Lodge became involved in the financial scandals that nearly bankrupted the Vatican Bank. However, by this time the lodge was operating independently and irregularly; as the Grand Lodge d'Italia had revoked its charter in 1976.[73] By 1982 the scandal became public knowledge and Gelli was formally expelled from Freemasonry. HolocaustThe preserved records of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (the Reich Security Main Office) show the persecution of Freemasons.[74] RSHA Amt VII (Written Records) was overseen by Professor Franz Six and was responsible for "ideological" tasks, by which was meant the creation of anti-Semitic and anti-Masonic propaganda. While the number is not accurately known, it is estimated that between 80,000 and 200,000 Freemasons were killed under the Nazi regime.[9] Masonic concentration camp inmates were graded as political prisoners and wore an inverted red triangle.[75] The small blue forget-me-not flower was first used by the Grand Lodge Zur Sonne, in 1926, as a Masonic emblem at the annual convention in Bremen, Germany. In 1938 the forget-me-not badge – made by the same factory as the Masonic badge – was chosen for the annual Nazi Party Winterhilfswerk, a Nazi charitable organisation which collected money so that other state funds could be freed up and used for rearmament. This coincidence enabled Freemasons to wear the forget-me-not badge as a secret sign of membership.[76][77][78] After World War II, the forget-me-not[79] flower was again used as a Masonic emblem at the first Annual Convention of the United Grand Lodges of Germany in 1948. The badge is now worn in the coat lapel by Freemasons around the world to remember all those that have suffered in the name of Freemasonry, especially those during the Nazi era.[79][80] Women and FreemasonryFreemasonry, which is considered by many to be a fraternal organisation, is sometimes criticised for not admitting women as members.[citation needed] Since the adoption of Anderson's constitution in 1723, it has been accepted as fact by regular Masons that only men can be made Masons. Most Grand Lodges do not admit women because they believe it would violate the ancient Landmarks. While a few women were initiated into British speculative lodges prior to 1723, officially regular Freemasonry remains exclusive to men. While women cannot join regular lodges, there are (mainly within the borders of the United States) many female orders associated with regular Freemasonry and its appendant bodies, such as the Order of the Eastern Star, the Order of the Amaranth, the White Shrine of Jerusalem, the Social Order of Beauceant and the Daughters of the Nile. These have their own rituals and traditions, but are founded on the Masonic model. In the French context, women in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries had been admitted into what were known as "adoption lodges" in which they could participate in ritual life. However, men clearly saw this type of adoption Freemasonry as distinct from their exclusively male variety. From the late nineteenth century onward, mixed gender lodges have met in France. In addition, there are many non-mainstream Masonic bodies that do admit both men and women or are exclusively for women. Co-Freemasonry admits both men and women,[81] but it is held to be irregular because it admits women. The systematic admission of women into International Co-Freemasonry began in France in 1882. In more recent times, women have created and maintained separate Lodges, working the same rituals as the all male regular lodges. These Female Masons have founded lodges around the world, and these Lodges continue to gain membership.

Notes

As the Rosslyn Templars have now exceeded half-million (575,000) visitors (as at June 2007) to its web site it is an opportune time to reflect on the past and attempt to judge the future. What have we done well? What had we not done well? and where ought this site be in four years time? - the same length of time since it was created.

It is perhaps important to make clear some facts about this, the Rosslyn Templar site, so that no one is misled or mistaken as to its purpose and function. The Rosslyn Templars is a small group of Freemasons dedicated to researching Rosslyn Chapel. The group is self-funding and is entirely independent of any other group whatsoever. So, although all members are Freemasons they do not act for or represent any other group of Freemasons. Nor do they have any connection with any particular branch of Freemasonry such as the Scottish Masonic Knights Templar whose governing body is the Great Priory of Scotland. This decision was made in order to maintain a strict independence from any other Masonic organisation.

In order to make available the research conducted by the Rosslyn Templars to a larger audience it was decided soon after being formed to have a web site. This went online in 2002 with one specific aim in mind - to investigate Rosslyn Chapel and all the subjects which have come to be associated with it - such as Freemasonry, more particularly Scottish Freemasonry, the Knights Templar and book reviews on relevant subjects. The primary intention was to place the chapel in its historical and ecclesiastical context by providing relevant material (old and new) and then to analyse and discuss that material in an attempt to bring some clarity to the subject. The first step was to gather information about all the collegiate churches in Scotland and compare and contrast them with Rosslyn Chapel such as Crichton, Dunbar and Seton to name but a few. The initial task of identifying them and collating brief information on each was relatively straightforward and has been provided in tabular form as a comparison table. That table provides brief details of all the collegiate churches in Scotland and links to separate illustrated pages about each church. To go there click here or on the previous links. Whist the comparison table is complete, page details of all Scottish collegiate churches are still being created. Of the 42 collegiate churches separate pages are available for 23. The delay in completing this project has been caused by a number of problems. For example, the decision to use photographs taken by Rosslyn Templars.

Other matters relevant to Rosslyn Chapel such as Freemasonry, the St. Clair family, the Knights Templar (as examples) were thought too important to be ignored and ought to be added to the site thereby delaying other parts of the site. The frequency of publication of books about Rosslyn Chapel was something never anticipated and came as something of a surprise. This phenomenon is a subject worthy of examination in its own right and a first step has been to list books which consider Rosslyn Chapel and Freemasonry. As mentioned elsewhere this modern phenomenon began as long ago as 1982 and shown no sign of abating. The Da Vinci Code (2003) is recent example (albeit a work of fiction) and The Rosslyn Hoax? (2006) is one of the latest works of non-fiction.

However, the main problem was simply due to the success of the site. A nice problem to have we admit, but the sheer number of enquires on a whole host of different subjects made serious demands on our time - time we never anticipated spending. We have tried to deal with as many queries as possible but with the best will in the world there is a limit to what a handful of people can do. To all those people out there who have sent e-mails and received no reply - we apologise. It has not been deliberate but we receive far more e-mails than we can cope with. It was thought that one solution to the problem would be to set up pages devoted to particular subjects such as those on the Knights Templar, the St. Clair (Sinclair) family, book reviews and much more besides. All that did was increase the number of visitors asking even more questions on subjects not previously covered by this site!

What then was the reason this site was created in the first place? It was created in 2002 as a direct response to the amount of material being published in the public domain about Rosslyn Chapel, Freemasonry, the Knights Templar, St. Clair family etc. Unfortunately, much of this discussed Freemasonry third hand, that is, by people who were not Freemasons and often almost as if Freemasonry did not exist in the modern era. This web site therefore has another subsidiary purpose - to have some Masonic input to the debate about Rosslyn Chapel and subjects which have come to be associated with that structure especially Freemasonry.

However, the creation of the group known as the Rosslyn Templars and its web site was no 'knee jerk' reaction to the writing of non-Freemasons on Freemasonry. The interest of non-Masons was created (certainly in the modern era) a little over 20 years ago with the publication of the book: The Holy Blood and The Holy Grail (1982) by Michael Baigent, Richard Leigh and Henry Lincoln but interest was dramatically increased with the publication of: The Temple and The Lodge (1988) by the same authors (minus Lincoln). That book was the first to argue (in great detail) that there was a link between Rosslyn Chapel and Freemasonry. These books spawned a large number of others on a similar theme. Interest in Rosslyn Chapel increased again with the publication of the novel: The Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown (2003). The film by the same title was released on 19th May 2006 increased, yet again, visitor numbers enormously. The film did not do too well at the box office but it, together with the release of film on DVD on 16th October 2006, has had a further impact on the chapel. An example of this is that on 16th November 2006 Rosslyn Chapel Trust was forced to advertise for more guides to escort the increasing number of visitors. November is hardly the height of the tourist season! One can only imagine what the summer of 2007 will bring in terms of numbers.

There can be no doubt that these books, fictional or otherwise (and now a Holywood film), have asked a number of provocative, speculative, questions and these have stimulated a debate that would not have otherwise existed. In our view that is one of the most positive aspects of these publications.

Unfortunately, the plethora of such books, articles (and even a movie) for sale in the public, rather than the much more critical academic domain, has given rise to many untested hypotheses regarding Rosslyn Chapel, the Knights Templar, Scottish Freemasonry that it has become very difficult to separate fact from fiction. This web site is therefore also an attempt to bring some clarity to that muddled, debate. One advance in that respect is the publication of a new book: The Rosslyn Hoax? by the Curator of the supreme Masonic body in Scotland - the Grand Lodge of Scotland - the home of Scottish Freemasonry. More details about this will be found on the News page including links to an interview with the author of The Rosslyn Hoax? It is significant that a book about Rosslyn Chapel and Freemasonry (Scottish Freemasonry to be exact) has been written by an eminent Scottish Freemason as opposed to non-Masons.

The Rosslyn Templars are devoted, therefore, to the promotion of the interpretation and understanding of Rosslyn Chapel from a number of different disciplines. The profit motive has no part to play in the work of the Rosslyn Templars or this web site although we hope that some will be moved to make contributions to charity. Details of the Rosslyn Templars' appeal for such donations will be found on the page named CHARITY.

The site now contains information not only on Rosslyn Chapel and Freemasonry, particularly Scottish Freemasonry, but also the Knights Templars (or Templars, or KT) and other material considered to be in some way connected to Rosslyn Chapel. The need to set the chapel in its Scottish ecclesiastical and historical context by providing information on all the other Scottish Collegiate Churches is half way to completion. The site has therefore become much larger than originally envisaged.

Where then should this site be in another four years? First and foremost the provision of details on the remaining collegiate churches is a priority but is, we freely confess, progress painfully slowly. Reviewing all the books which deal with Rosslyn Chapel is also something that is desirable although that is a time consuming task. We have also been made aware that the site lacks internal links which would allow visitors to more easily move from page to page. Such links to, for example, Book Reviews are shown in this manner and will be added to more pages as the site is updated. If past experience is anything to go by then it is inevitable that something will come along to delay our plans but that ought not deter us from setting goals and plans to achieve them. “Freemasonry and Democracy”

by Brother C. Martin McGibbon, Grand Secretary of the Grand Lodge of Antient Free and Accepted Masons of Scotland.

Whilst Freemasonry as an institution is, and always has been, strictly non-political and non-religious, we always have had amongst our membership individuals who were active in political life and in the various religions of the world.

I would emphasise that our membership includes individuals from all the World’s faiths, including Christians of all denominations and we always have had, over the years, members of the various political parties active at the time.

I am delighted when members of our Order, including those in prominent public positions, such as MSP’s, voluntarily choose to acknowledge their membership of our Order. Freemasons are encouraged in terms of our own ‘Rules and Regulations’ to acknowledge their membership on all proper occasions but I do have difficulty with any form of compulsion being placed upon individuals to ‘force’ them to register or declare their Masonic Membership.

Democracy and Freemasonry are found together wherever governments believe in tolerance and the right of citizens to a private life, including Freedom of Association.

The first President of the United States, George Washington, was a Freemason. Indeed, it was Freemasons from Edinburgh, who were also stonemasons, who built The White House; a Scotsman, who was Grand Master of the Freemasons of New York, laid the foundation stone of the Statue of Liberty and many Scottish Freemasons have made a lasting contribution in other democracies, for example in Canada, New Zealand and India.

Many famous Scots were proud to have been Freemasons, for example, Robert Burns, Sir Walter Scott, Adam Smith and very many more.

However, it should be borne in mind that for every famous individual who was, or is, a Freemason there were, and are, many, many more ‘ordinary’ members drawn from all walks of life.

Many old Scottish Lodges, such as George Washington’s, are still in existence and are cherished by the Freemasons in those countries.

Scottish Lodges exist in countries as diverse as; Malaysia, New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, Botswana, Jamaica, Chile and India - to name but a few. Indeed there is not a single continent where Scottish Freemasonry does not exist. Scottish attitudes and culture are therefore disseminated across the democratic world and Freemasons in these countries are proud to be SCOTTISH Freemasons.

Freemasons (whether Scottish or otherwise) throughout the world look to Scotland as being the home of Freemasonry. Each year many thousands visit this country to attend meetings of the Grand Lodge of Scotland and the Masonic Lodges here ‘at home’, making a useful contribution to our national tourist industry.

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

IJ

K

L

M

N

P

R

S

T

V

W

Y

Here we list a few Famous Bristish Freemasons but it extremely important to appreciate that for every famous Freemason there are and were thousands, if not tens of thousands, of 'ordinary' Freemasons.

References

|

| |